It just ratchets up, doesn’t it? The climax of a tight Test match ratchets up the tension and anguish to the same point a normal sport can take you… and then it just gleefully and sadistically carries on ratcheting from there. It keeps on ratcheting for maybe another hour of ever-escalating torment, beyond what you thought was possible; beyond what a person should be asked to take in the name of entertainment. And then, one way or another, that tension breaks.

If you’ve been following your team for years and the Test in question for hours and days, you’ll have pretty strong feelings about which way you want that tension to break. It went the wrong way for England fans this time around – although it could have been worse. The 2005 Edgbaston finish actually had too much riding on it. We don’t want to be in a situation where a match like that goes against us. This one was bad enough.

We’ll take it though. This was a good and just-about-manageable level of stomach-churning impotent desperation.

Long form drama

There’s a reason why it’s more dramatic when someone’s trying to kill Stringer Bell or Adriana La Cerva compared to an attempt on the life of Unnamed Security Guard or Henchman Number 6. Whatever you feel about major characters in a story you’re following, you get to know them and that’s important.

It’s the same with a Test match. A lot’s happened. You’ve put a lot into this.

You’ve watched the highlights. You’ve followed the score. You’ve delighted in Harry Brook’s breathtaking dobble and you’ve tried to explain Ben Stokes’ declaration to pretty much everyone you know.

But it’s not just the hours of play. You’ve looked forward to this series for a while and you’ve poured more time in overnight too (such an important and underappreciated part of the Test match experience).

Where’s Mitchell Starc? Where’s Ben Foakes? Is David Warner going to be crap again? Are England going to end up looking a bit fast-medium at some point?

There’s also all that time you’ve already invested watching these players down the years. You’ve taken in a lot in that time. It’s all in there. You’ve seen these people change and grow. Jimmy Anderson has lost a quarter of a yard of pace since you saw him open the bowling for Lancashire in 2002, for example.

That’s why when you see Stuart Broad high-stepping in to a hat-trick ball crescendo even when it’s not actually a hat trick ball, it’s not just Stuart Broad. It’s 8-15 Stuart Broad, Courier Mail under his arm, the greatest batter in the world.

When David Warner leaves one outside off stump, it’s not just David Warner. It’s David “Sandpaper” Warner, Ashes brutaliser and Ashes brutalisee.

When Moeen Ali daubs another stripe of pus on the pitch from his raw spinning finger, it’s not just Moeen Ali. It’s Polyfilla Moeen, the magnificently malleable peg who filled every hole in the England team for all those years, back one last time for just some of the glory he’s still owed.

When Usman Khawaja finally – finally – gets out, it’s not just Usman Khawaja. It’s Usman Khawaja, born in Pakistan, qualified commercial pilot, seemingly dropped for good but given one last Test thanks to someone getting Covid, at which point he started uncontrollably vomiting endless hundreds.

When Jonny Bairstow misses a stumping off Moeen, it’s not just Jonny Bairstow. It’s England’s greatest one day batter, the man who launched England’s recent renaissance and a man who, if you know what he suffered as a child, you can’t help but wish experiences nothing but happiness for the rest of his life.

With such rich characters and plenty of plot twists and turns, it’s only natural that we should find ourselves emotionally involved in this chapter. We don’t just follow the climax, we feel it.

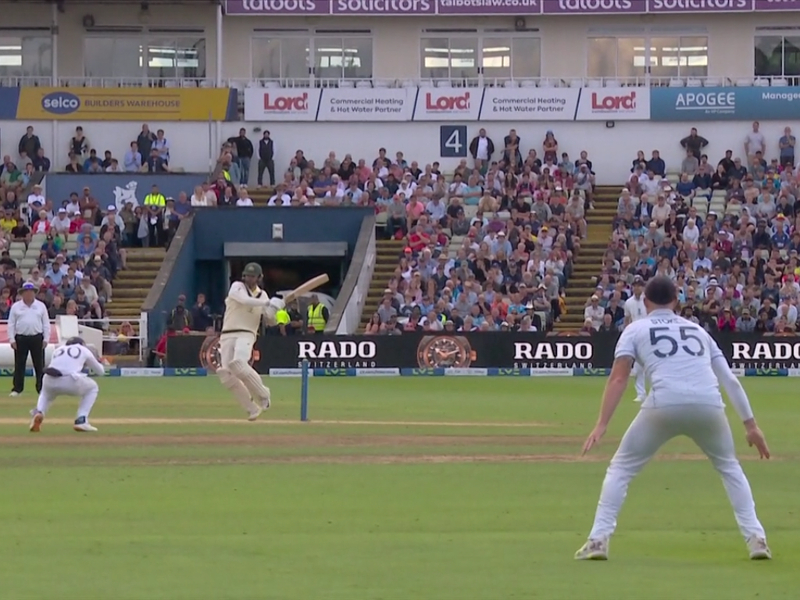

So finally, after four and a bit days of play, it’s down to this: Pat Cummins and Nathan Lyon and their damn edgeless bats, sashaying around slotting runs into the endless empty green spaces of Edgbaston.

The cricket itself is unremarkable. The cricket is also absolutely excruciating.

Pat Cummins, early injuries, unshakeable decency and endearing sledging. Nathan Lyon, the poor guy who dropped the ball at Headingley in 2019. Is that right? Maybe for you it’s Nathan Lyon, the absolute prick who dropped the ball after that other run-out a year earlier.

It doesn’t really matter which. That only influences what you feel, not how much.

Follow King Cricket by email – unless you already do, in which case maybe buy us a pint? Frankly, we could do with one.

I was awake at half 10 last night, still cross about England’s loss in that test. The thing is though, I’m still annoyed at England’s 72 all out in Abu Dhabi in 2012 so I’ll probably be recovering from Ben Stokes’ first day declaration sometime in 2024 or so.

Wondering if we can ask the boards to skip this series and only hold the Ashes in Australia so all this gut-wrenching tension and despair happens while we’re asleep.

Ah, the Daily Telegraph letters page…

All of these letters were signed Capt. J.P. Dibcock (retd.), and all were postmarked Godalming. At least, I assume they were. It’s not like I’ve actually read the Telegraph’s letters page. These are just quotes from that repository of righteous anger that came up on my MSN feed.

Some context. England lost by two wickets.

How bad do you have to think the #1 ranked team and current test world champions are, that they could only beat a side who were brainless, foolish, ridiculously bad, reckless and lacking in genuine pace by two wickets? Imagine if we’d only been brainless and foolish; we’d have won by an innings!

Some Gilbert and Sullivan to finish:

Nobody has written poetry that good since 1881, and nobody ever will.

Quite. Think England should aim to be merely ridiculously bad next Test and waltz to victory.

This is what these people say when a change in approach has taken England from uncommonly awful to achieving unprecedented feats basically overnight. Imagine what they’d be saying if England were, say, only 50% better than 18 months ago.

It makes sense to them, that older way of playing. It’s something they can understand. Results don’t matter, all that is important is that test cricket continues to be exactly the same as it used to be. The same is true for sandwiches, and music, and trousers, and the colour of your neighbours. It’s why standard golf attire is essentially smart-casual from 1970.

Sandwiches, or sand wedges?

I can understand (and share) the profound disappointment, but I cannot understand anger with England’s tactics and England’s narrow loss in the Egbaston test.

Andrew Miller’s editorial piece on Cricinfo, though long, sums up the topic well:

https://www.espncricinfo.com/story/ashes-2023-forget-the-frivolous-narrative-bazball-is-a-hard-nosed-winning-strategy-1382773

It is possible, Bert, to applaud a modern approach to the game of cricket while also nurturing a love of early music and a tendency to retain old pairs of trousers.

With any luck, they will select Rehan Ahmed for the next Test so we can once again debate whether he really is younger than Ged’s old cricket troos.

For those bemused by these references, KC’s piece about “things older than Rehan Ahmed” can be enjoyed here:

https://www.kingcricket.co.uk/six-things-older-than-rehan-ahmed/2022/12/21/

My cricket troos is but one example in the piece.

But the relative antiquity of my cricket troos is no longer a matter of debate, Sam. They have been subjected to a modern form of carbon dating (silicon dating) and can be unequivocally identified in my possession and on the field of play in June 2001. Rehan Ahmed was born in August 2004.