Shane Warne said he always used to try and really rip a leg break when he first came on to bowl. This wasn’t to try and dismiss the batsman – although sometimes it did – it was really just to sow a seed of doubt. Warne wanted to maximise the range of what his opponent thought was possible.

This is what sharp spin does. It expands possibilities.

Enough turn

Some people say you only need to turn the ball the width of the bat to find the edge. This is sort of true. But there’s a ceiling to how threatening you can be if that’s the maximum deviation you can muster.

Facing a bowler who turns the ball ‘just enough’, the batsman will probably feel pretty confident in his choice of shot whether the ball turns or goes straight.

Conversely, if what at first looks like the same delivery could arrive at the batsman here or *all the way over there* then the same batsman is most likely making his initial movements with two entirely different shots in mind.

Throw in a googly or some other kind of delivery that spins the other way and you increase the range of possibilities further. Suddenly the batsman is half-playing three shots as the ball travels from the bowler’s hand.

That’s when batsmen start looking like idiots and that’s why wrist spin is great.

Extra skid

The amount the ball turns increases the range of possibilities. But that’s just one variable. Deliveries can also arrive at different speeds.

To a very great extent, speed comes from the hand. But as with turn or late swing, much of the danger comes with changes in pace as the ball pitches – particularly if there is a lot of variation.

Batsmen are like drummers. We don’t just mean that their job is hitting things. They’re also very rhythmical creatures.

When a batsman is ‘in’ and seeing it like some sort of ball that is famously larger than a cricket ball, a large part of the apparent ease of batting is because they’ve found a rhythm. After facing a lot of deliveries, they get a very precise feel for how long it will take for the ball to arrive at them after pitching and their body starts to work to this time signature.

But what if that timing varies? What if it varies markedly? And what if that marked variation also coincides with marked variation in how much the ball turns?

The all-rounder’s view

Speaking after the two-day day-night Test in Ahmedabad, Joe Root said he felt that the thick shiny lacquer on the pink ball had been a more significant thing than the pitch.

“I honestly think the ball was a big factor in this wicket – the fact the plastic coating, the hardness of the seam compared to the red SG meant it gathered pace off the wicket,” he said.

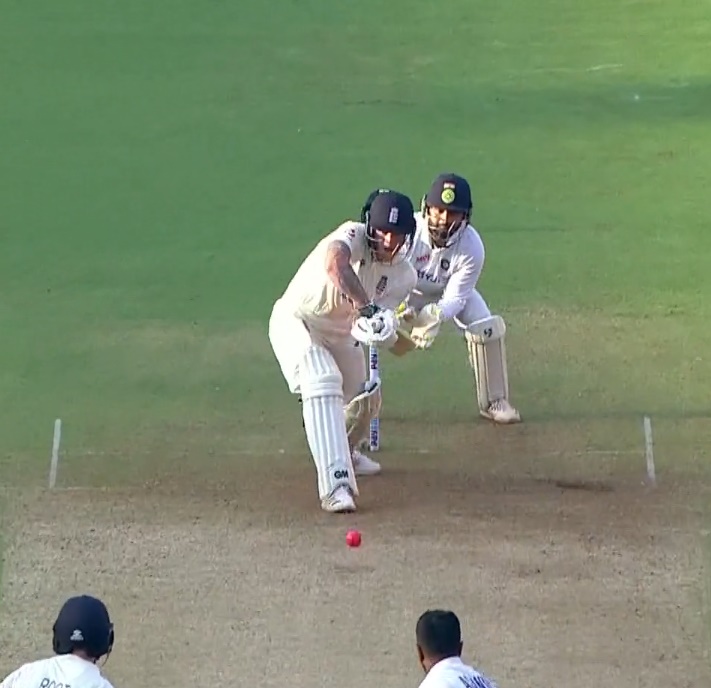

“If it hit the shiny side and didn’t hit the seam it almost gathered [speed]. A lot of those wickets on both sides, the LBW and bowleds, were due to being done for pace beaten on the inside.

“If you look at some of the replays, batsmen probably ended up in the right position but because it was gathering pace off the wicket it was difficult.

“Credit to Axar [Patel] in particular – I think he exploited that really well and found a very good method on that surface.”

What Root is basically saying here is that even if the pitch were true and spun consistently, the ball resulted in unmanageable variation.

Two deliveries that looked the same – and which may even have been bowled in the same way – could arrive at the batsman completely differently. One would arrive early and straight and the other would arrive much later and wider.

There are things a batsman can do to try and mitigate that, and – as Root said – there are also ways to bowl where you can better exploit that. As such, you can argue it’s still a fair contest between the two teams.

There is no real route to success for batsmen though. By playing a different way the odds can be shifted from terrible to bad, but they can’t really be improved much above that.

Unpredictably varied speed combines with unpredictably varied turn to increase the range of possible outcomes beyond what it’s credible to counter.

That would seem a valid criticism of using a highly lacquered pink ball on a pitch offering good turn – that for even a good batsman, it’s a puzzle with no real solution.

We’re on Twitter. You’re very welcome to follow us.

Very well put, KC. The pink ball had a lot to do with making the pitch look worse than it was.

I felt that the batsmen could’ve used their feet more, Axar for instance playing in his second test was hammering away at the exact same spot all through, England could’ve put pressure on him and asked him to vary his lengths by making use of the crease and coming down the wicket. Pujara does this to Lyon who also likes to plug away in a similar area.

Second, batsmen should’ve put away horizontal shots, there was no cutting or sweeping here if there’s no way to know the eventual line.

Third, batsmen needed to be proactive overall – singles, doubles, aggression – knowing there’s a delivery with their name on it around the corner.

Fourth, also be patient for the lights and dew to come on, making batting that much easier.

This wasn’t a 400 plays 400 wicket, but it was surely not a 110 plays 140 wicket either.

I would say pink ball on a turning wicket adds another puzzle for international batsman, with a big learning curve, but definitely not an unsolvable one, IMO.

I thought Rohit’s in both innings and Stokes’ batting in the second innings would be good templates for batsmen from both teams – protect your stumps, be unfazed by any spin beating you, use your feet when possible, do not cut pull sweep, yet always look for runs.

A bit like how an earlier generation of batsmen eventually figured out how to play Anil Kumble.

Stokes’ innings was instructive in that he did a lot right and not really very much wrong and was out for 25. We absolutely agree that most of the batsmen could have done more, but that innings did give a sense of the limits of what could be achieved. You’d probably need a good few things to go your way to score much more than that.

It was quite a steep learning curve for a Test match, in terms of presenting players with new conditions to adapt to. With the pink ball in the mix, it seemed quite markedly different from playing on even a normal ‘turner’.

well summed up there KC.

I feel far more EW Swantonish than I am comfortable with after that test. They should probably change the Test Championship rules in response; it’s weird you can be docked points for a slow over rate but not for preparing a pitch that turns a test match into a farce, however entertaining. And it wasn’t really that entertaining.

Very uncomfortable feeling Swantonish. Most disconcerting.

Day night tests are still a new thing so maybe it’s inevitable that there will be weird games like this.

It does feel like this was the first time there was this combination of ball and pitch. It’s weird that Tests are the, um, testing ground.

Maybe it’s weird that we’re seeing innovation applied to Tests without thoroughly honing the format through experimentation in the domestic game, but it also tells us something a bit sad about first-class cricket, I think – that it’s now deemed so uncommercial that it’s not even worth the potential boost. Just seems to be accepted first-class competition is financially pretty much a write-off whose primary purpose is to develop Test players for Team England (and suspect something similar elsewhere in the world), with a sideline of maintaining a hallowed tradition and giving the players something to do between limited-over fundraisers. Cricket in county whites feels more akin to a historical sport recreation society, rather than a potentially dynamic, sellable product that’s due a modern-life-friendly refresh. (Are many county grounds under local restrictions for how many evenings per year they’re allowed floodlights, and has that been a factor in why the concept’s not really been pursued much further?)

Every experiment with day/night first class cricket in England, be it the test match or the county championship round, has been freezing cold and therefore very off-putting at night.

If you want bang slap in the middle of the summer, when there’s a better chance of warm evenings, the nights are long here in England making the “glorious floodlit” effect marginal or even irrelevant. There are floodlight restrictions for some grounds, but those are almost as irrelevant as the lighting the emanates from the floodlights for much of the summer. Even Lord’s has managed to convince the local authorities to release the restrictions, given that the concerns were really about noise/crowds at night more than the lights themselves. My guess is that most locals (other than those who like cricket) wouldn’t even notice most county championship days, with the hundreds (or low thousands) drifting in and out throughout the day.

I think floodlit day/night first class cricket has a future pretty much everywhere in the cricketing world except England (& perhaps New Zealand).

The commercial viability of first class cricket in England (& elsewhere) I think is a separate point, Bail-out.

Interesting, Ged. Cheers.